“Digital ethics: In some contexts, we shouldn’t use autonomous systems at all”

Digital ethics // Oliver Bendel has been researching and publishing books on information, robot and machine ethics for many years, and has been invited to speak as an expert at the German Bundestag and European Parliament several times. We talked to him about the opportunities associated with AI, the morals behind the machines, plus the concepts of guilt and responsibility with autonomous systems.

Mr. Bendel, does the development of AI worry you? What do you consider to be the biggest threats of AI?

I’ve been working in AI since the 1990s. I’ve never been worried in all that time. Also, worry is a poor basis for making decisions. I can’t speak about the risks of AI generally, since there are so many different systems and applications. In our work we describe text, image and video generators and identify the opportunities and risks. We also look at facial and voice recognition.

Which ethical aspects do you find the most concerning in relation to AI?

Some forms of AI are very powerful, such as generative AI. You can use them to invent new poisons and warfare agents. But you can also use them to develop new medicines. In the future, we’ll use AI systems to fight disease. Meta wants to use AI to observe, measure and analyze the biological and chemical processes within the human body. It’s essential that we consider the ethics of such applications.

What actually is artificial intelligence? Is processing big data and using it for the statistical calculation of probability intelligent by definition? Is ChatGPT intelligent?

Artificial intelligence is a specific field of computer science that studies human thought, decision-making and problem-solving behavior in order to then map and replicate this using computer-supported processes. The term can also refer to machine intelligence itself, so artificial intelligence as both an object and a result. This wide-reaching term also covers conventional, rule-based chatbots. And of course ChatGPT, which uses machine learning, or more accurately, reinforcement learning from human feedback. It’s not about machines being intelligent in a human sense. It’s about them mapping and reproducing human intelligence using technical tools.

Does the fact that AI only simulates human intelligence mean that the systems can never become more intelligent than humans?

AI systems can also simulate animal intelligence. Or an imagined intelligence, as it could be in the case of superintelligence. AI systems could surpass human capabilities, no question about it. They’ve been doing it for years already, just look at chess. If we look at intelligence as a complex system unique to particular living beings, of course you can say that AI can’t achieve this level of intelligence. To do that it would have to become like those beings. But if we consider particular aspects of this intelligence instead, then AI surpasses us on a daily basis.

People like to project anthropomorphic concepts like morals and feelings onto other entities. When a baby’s born, suddenly the cat’s jealous. And we think chatbots are unethical because they lie.Is it wrong to want to transplant human concepts to machines and is it maybe too idealistic to set higher ethical standards for machines than for humans?

It’s true that we anthropomorphize. Like when we talk to or name our cars. It’s a natural human quirk. But sometimes we don’t just project something onto machines, we plant something in them. That could be artificial intelligence, artificial, morals or artificial consciousness. That’s the other side of anthropomorphization: We choose human characteristics and reproduce them in computers. For many years in the context of machine ethics we’ve been building ‛moral machines’. They follow certain moral rules that we give them.

But it’s also true here that morals themselves are simulated. Put quite simply, they’re machines, without consciousness and without free will. But to some extent, they can do more than animals can — they can weigh up different options and then make the right decision, one that we hopefully see as a good one. That doesn’t mean that the actions of the machines are good or bad in the human sense.

Can you give us an example of a moral machine like this?

In 2016 we built the LIEBOT. It uses seven different strategies to generate lies. After input from the user, it looks for a correct answer and then manipulates it. It does this with a focus that we generally assign to software agents. I don’t find it problematic to use the word 'lies' here. If we didn’t allow these kinds of metaphors and let them solidify into technical terms, we’d barely be able to talk about these things, especially new ones. A few scientists want to set higher standards for machines. For example, they think that unlike us, machines should consistently and reliably adhere to moral codes. And that machines should even set an example for us. Susan L. Anderson and Roland C. Arkin embrace such ideas. I respect and understand the approach of these two machine ethics specialists. But I have a different view. For me it’s about transferring individual moral beliefs to machines. One of the methods we use for this is moral menus.

The term ‘alienation’ plays an important role in European intellectual history, whether it’s the alienation of nature or work. AI and the Internet of Things have the potential of alienating us from our own bodies, and even more so from our direct environment. Like when a smartwatch reminds you to have another couple sips of water because it’s 28.6 °C and 56 % humidity. Does that worry you?

Tools and media can threaten to come between us and reality, to change reality and our perception of it. We are biological beings and at the same time cultural artefacts. If we became cyborgs, the blending of the natural and artificial would become even more evident. Sometimes we should rely on our instincts.

Does AI influence our perception of responsibility and guilt when the actions of autonomous machines lead to damage?

Autonomous systems can’t be held responsible. So equally, they can’t be called ‛guilty’. For years I’ve said that we can't and shouldn’t forgive machines for anything, unlike how we forgive people. Richard David Precht looked into this notion at a summit in Düsseldorf in fall 2023. It’s always humans that bear the responsibility. The question is, which human? An AI system can have inventors, manufacturers, managers, and hundreds of developers, not to mention the operators and users. I think in some contexts, we shouldn’t use autonomous systems at all. Then it would be much simpler, not least when it comes to assigning responsibility.

In the US I think it’s possible to program an autonomous vehicle so that it will swerve right to run over an old man rather than left where a whole kindergarten class has just sat down for a picnic. Do we need to start talking about these things here in Europe if we want to take the development of autonomous systems seriously?

We’ve been discussing this in Europe for about ten years. I first looked into it for a talk I gave at the start of 2013 in Prague. In 2012 we developed a formula for autonomous cars that can quantify and qualify, and advised against its use. The then Federal Transport Minister, Alexander Dobrindt, established an ethics commission in 2016 that came to the same conclusion. We’ve been building moral machines for many years but that doesn’t mean all autonomous machines need to be like that. At least not when it comes to humans. For animals, I can see possibilities that I’ve been working on since 2013. So emergency braking and swerving could be used not just for large beings, but for small ones too, like tortoises and hedgehogs — as long as it wouldn’t endanger any road users.

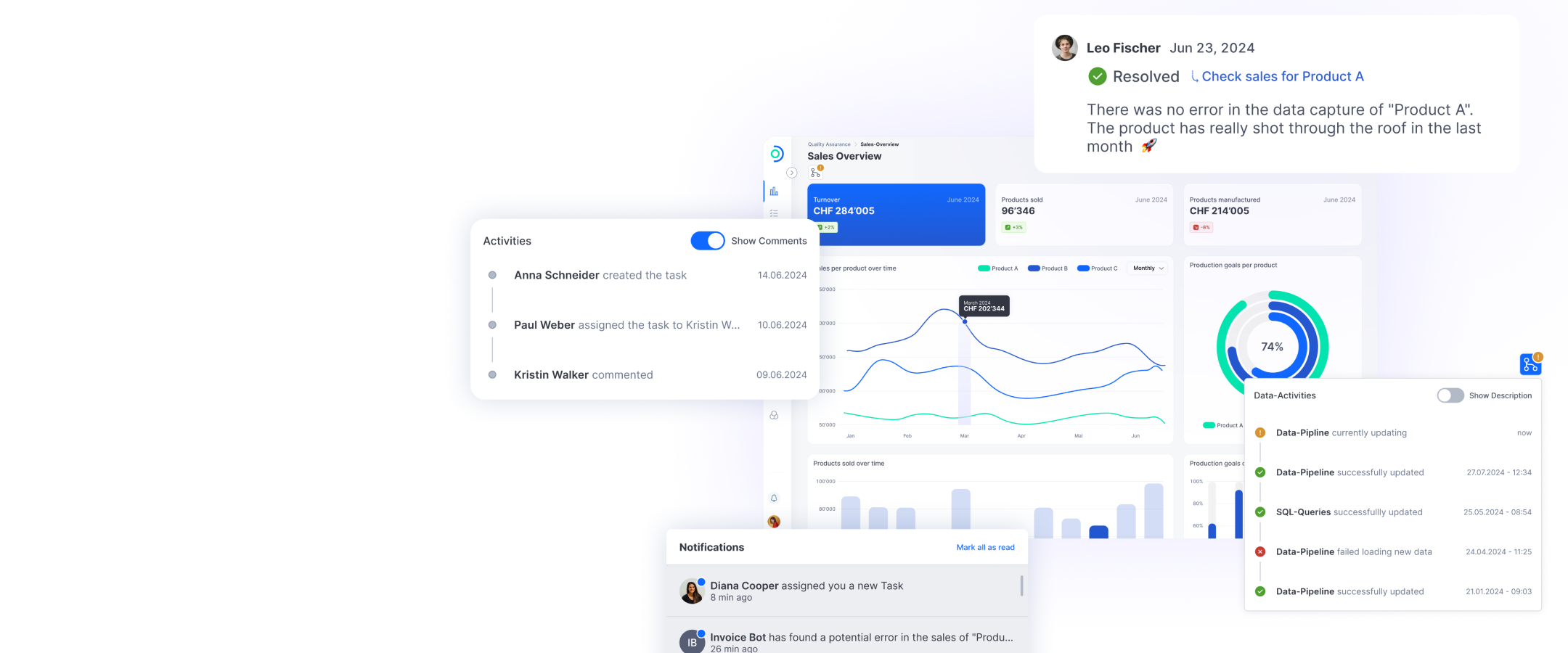

When it comes to AI systems, again humans are responsible. But which humans? The creator, the builder, the manager, or the hundreds of developers? Or even the operators and users?

Do you think that AI has the potential to make the world a better place? Or will it just follow in the footsteps of lots of previous innovations and make us more productive?

I think that neuronal networks, language models, and particularly generative AI, can solve a lot of problems, but can also cause them. Ultimately they’ll be hugely beneficial for us and we shouldn’t miss out on them in our role as ‘Man the Maker’. Thanks to new AI systems, we’re getting closer to the universal machine. For me that’s a connected robot that can manage and solve numerous problems in daily life. Elon Musk’s Optimus is headed in this direction — but for that, you first need a talented designer.

Humans have been developing machines to take work off their hands since the age of sedentism around 10,000 years ago. And now we’re suddenly worried there’ll be no work left. Is that a paradox?

We idealize work and problematize the tools. We orient our lives around the needs of businesses, not our own needs. We need to rethink work. If we let the tools do the work, we can spend our time doing what we enjoy. I’m sure there’ll suddenly be lots more scientists and artists. We won’t just be lazing around.

AI developments predominantly come out of the US, with Europe lagging behind. What can be done?

They’re also coming from China, but the US certainly has the edge in terms of generative AI. In Europe we’ve neglected AI and robotics for years. We’ve sold companies and cut back on research. Right now that’s changing. Companies are being bought back and robots retrieved from the scrapheap. One of the driving forces behind this is the United Robotics Group. Modern service robots are often connected to AI. At the same time, you have to rely on your own language models, like Aleph Alpha. These are also relevant for robotics.

In what way?

That’s one of my favorite topics at the moment — how can we use language models for industry and service robots? I don’t mean natural language communication between human and machine, but new perception and control models. Robots move through their environment and learn about it. The image data and audio data are incorporated into the language model. When you input a prompt, by giving the robot an order in natural language, it’s processed like you’re used to from text and image generators. But in this case, not virtually, but physically. Without any prior time-consuming programming. These are exciting times for our sciences — for robotics and AI as well as ethics.