Open by default: It’s the law

Open source and open data // A new Swiss law will require the federal administration to publish all of its software as open source software. Public authorities will also be required to release their data as open government data. The new law is creating more openness, boosting innovation, and prompting a cultural shift in the federal administration. Plus, more digital public goods means more digital sustainability.

Switzerland’s National Council and Council of States adopted the Federal Act on the Use of Electronic Means for the Performance of Government Duties (EMBAG) in March 2023. The new law is expected to enter into force on January 1, 2024. It will serve as Switzerland’s new digitalization law for its central and decentralized federal administration. It makes “digital by default” a requirement (Art. 3) and creates the legal basis for other aspects such as standards, interfaces, interoperability, and pilots (Arts. 12 through 15). One crucial aspect is the law’s new provisions for the federal administration’s software and data. First, under the EMBAG, the federal administration must make programs and modules developed by its own employees or outsourcers available as open source software, or OSS for short (Art. 9). Second, the EMBAG requires the federal administration to release all government data as open government data, or OGD (Art. 10). Here the law provides important exceptions for personal data or data that is relevant to security. These two “open by default” rules are prompting a significant paradigm shift toward more openness and transparency. They will also make reusing software and data much easier. This is creating many opportunities for the federal administration and businesses – but challenges also lie ahead.

The politics behind the release of open source software

Switzerland has been debating whether the federal administration should publish OSS for over 12 years. The Federal Supreme Court initiated the discussion in 2011. Back then, it published its OpenJustitia application under an OSS license. Its aim was to allow other courts to use the legal software and save tax revenues as a result. The company Weblaw didn’t like this. It wanted to sell its proprietary software to cantonal courts. It claimed that the Federal Supreme Court was competing with it. This prompted a heated discussion in the following years. Both political initiatives and legal opinions considered the questions of whether and, if so, when the state should release its own software under an OSS license. In the end, lobbying by the Digital Sustainability parliamentary group (Parldigi) and successful open source development work in the IT industry led to the EMBAG. The new law not only permits the release of OSS. It actually makes the publication of the source code an obligation “unless the rights of third parties or security considerations would exclude or restrict this.” So, in the future, all federal agencies in Switzerland have to think about publishing OSS. The EMBAG creates the ideal legal framework for implementing the demands of the global campaign Public Money, Public Code. At the same time, releasing OSS also benefits external IT service providers because it lets them use the software they have developed for the federal administration in projects for other clients.

Why “by default” matters

It’s still unclear what key requirements will apply to the publication of OSS. A practical guide to OSS in the federal administration was drawn up in 2020. The Digital Transformation and ICT Steering section of Switzerland’s Federal Chancellery manages these guidelines. However, the section on “Releasing OSS” currently states that federal offices themselves are responsible for whether and how they publish OSS and collaborate with communities. In other words, clear specifications and recommendations on how federal agencies are to implement Article 9 of the EMBAG are now urgently needed. The Canton of Bern is already a step ahead here. Its IT regulation has permitted cantonal offices to release their own software as OSS since 2018. The canton also published rules and checklists for releasing OSS. But the Bern example also demonstrates how, in reality, such laws alone result in the release of very few new OSS applications. Since 2018, just one application has been published on the Canton of Bern’s GitHub profile. The benefit-cost ratio of publishing OSS is usually too small for individual agencies. Plus, there still isn’t enough awareness of the benefits of OSS for the economy as a whole. As a result, administrative offices won’t put in the extra effort and release their internal applications as OSS unless they have to. This is why the “open source by default” rule in the EMBAG is helpful – now authorities have to meet this requirement. Releasing OSS is becoming the new normal.

“Open government data by default”

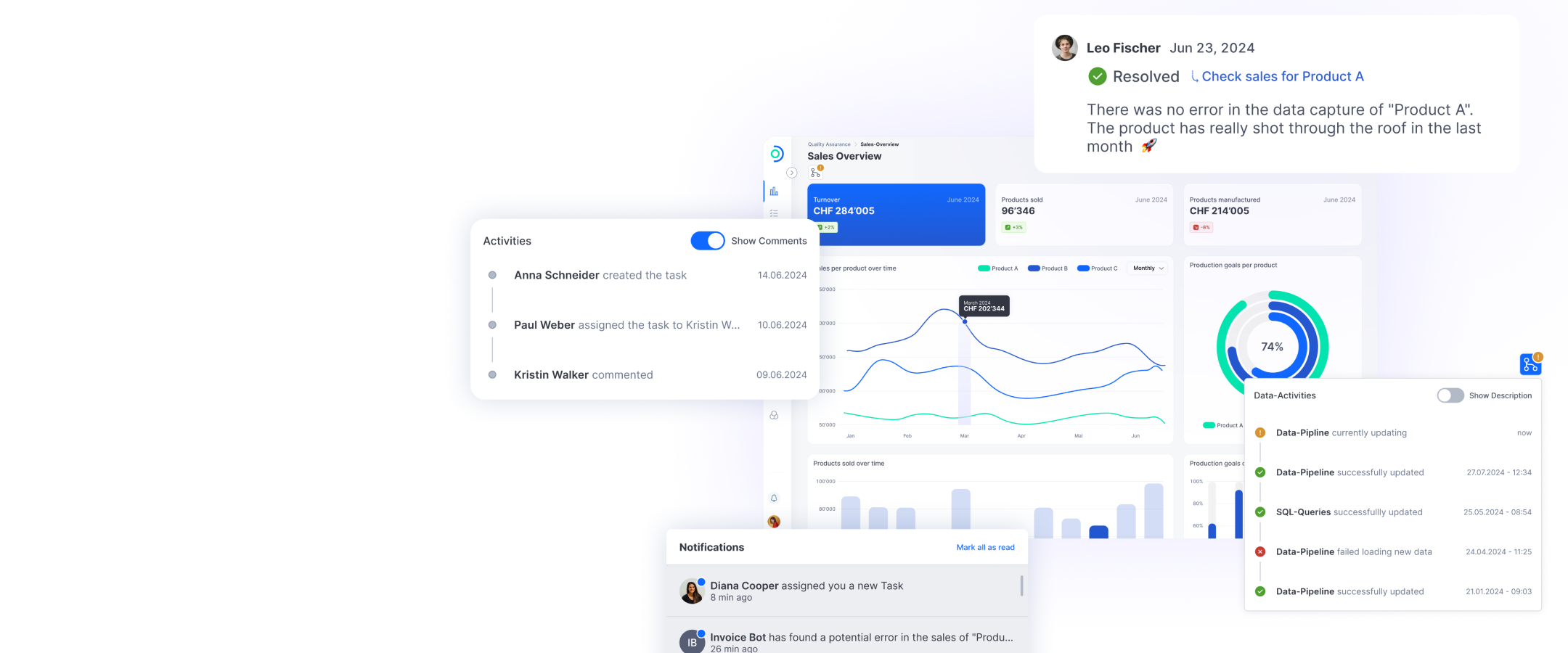

In addition to software, Article 10 of the EMBAG requires that the federal administration also release its data “by default” in the future. Just as with the release of OSS, the main reasons for this rule on open government data (OGD) are economic considerations and promoting innovation. The Parldigi parliamentary group also prepared the political groundwork for this topic over many years. There wasn’t any direct political resistance as there was with OSS. However, the Federal Council’s previous OGD strategies didn’t prompt most of the federal agencies to actually release any data. So far, the opendata.swiss platform includes data from just a few federal offices, even though this metadata portal already links to over 9,000 data collections from the public sector.

Some commentators hope that the “open by default” principle in the EMBAG will also lead to a cultural shift regarding OGD. In the future, federal offices are to publish their data at no cost, promptly, and in a machine-readable and open format. Any organization will be able to reuse this data for any purpose (Art. 10(4)). Beyond the specific challenges of OGD, these requirements are also prompting a general debate about data governance and data management. Administrative bodies now produce and use huge quantities of data, just as any company does. But it’s often still unclear who exactly is responsible for which collections of data and where exactly the data are stored and processed. Moreover, there is an absence of general rules guaranteeing interoperability, data security, and privacy. Releasing OGD in a professional way means addressing these and other challenges. But the necessary expertise is often lacking. The Federal Statistical Office (BFS), which is in charge of this area, has therefore launched intensive training for state employees. Its aim is to enhance their knowledge and experience in handling data.

It also has an OGD unit, which is expertly staffed and deals with the operational and strategic work of releasing federal data. This unit also networks with the cantons and municipalities. Unlike with OSS, OGD has a clear position within the BFS from an institutional and staffing perspective – the ideal starting point for implementing the OGD principles in the EMBAG.

What else is there to do? And how are other countries approaching it?

A good law is important. But what ultimately matters is how it’s applied in practice. Switzerland has made a lot of good progress in coordinating OGD activities. But when it comes to releasing OSS, there are still questions on the organizational and financial side. Many federal offices are already publishing a large number of OSS components and applications according to the OSS Benchmark. However, this is happening without any kind of coordination. Federal agencies need practical support because publishing OSS often raises technical, organizational and legal questions. Many institutions, such as the European Commission, have an open source program office (OSPO). These offices bring together the many different aspects of OSS within an organization. Setting up a “Federal OSPO” with the necessary resources and skills would therefore be a great step forward. This office could promote an exchange of knowledge, develop good practices, and foster networking. In particular, it could draft legally sound recommendations and criteria for procuring software in the future.

A look at other countries shows there is no need to reinvent the wheel. Germany, for example, set up the national portal Open CoDE so the public administration could share OSS. The German federal government, several states, and many municipalities have already published over 50 software solutions on the platform. This is advancing digital sovereignty in the workplace in public administration and other IT projects. Open CoDE is part of the German government’s activities around digital sovereignty. The German government has also set up a Center for Digital Sovereignty in Berlin. This center aims to connect the public administration with open source communities. It is headed by the Federal Government Commissioner for Information Technology.

France launched CodeGouv in 2021. This national initiative comprises numerous OSS applications, guidelines, and discussion forums for sharing lessons learned and specific IT solutions. With a budget of 30 million euros, France’s open source program carries out various tasks. One of these is making over 9,000 OSS repositories from more than 100 authorities available on the online portal.

Digital public goods promote digital sustainability

Open source software components and data fall under the category of digital public goods: they do not deteriorate (like physical goods) and do not exclude anyone (like private goods). The United Nations has adopted this defi nition. Like many others, the UN places digital public goods in the context of digital sustainability. Investing in and sharing digital knowledge is seen as crucial to sustainable development. The UN founded the Digital Public Goods Alliance in 2019 to promote this purpose. Besides OSS and open data, the alliance lists open AI models, open standards, and open content as examples of digital public goods.

From this perspective, the EMBAG provides a legal basis for creating more digital public goods. First, it will significantly boost digitalization by promoting innovation and efficiency in Switzerland’s federal administration. And second, it fosters sustainable development at the global level thanks to its “open by default” mechanism. So ultimately, the EMBAG also opens up new ways to unlock potential: the potential of digital sustainability – and this is a valuable and important task for the IT industry.